Partner, Portfolio Manager

Volatility returned to the market at the beginning of August. A lot of factors, many of which we have already discussed, weighed down domestic markets. One such factor we haven’t written about is the carry trade.

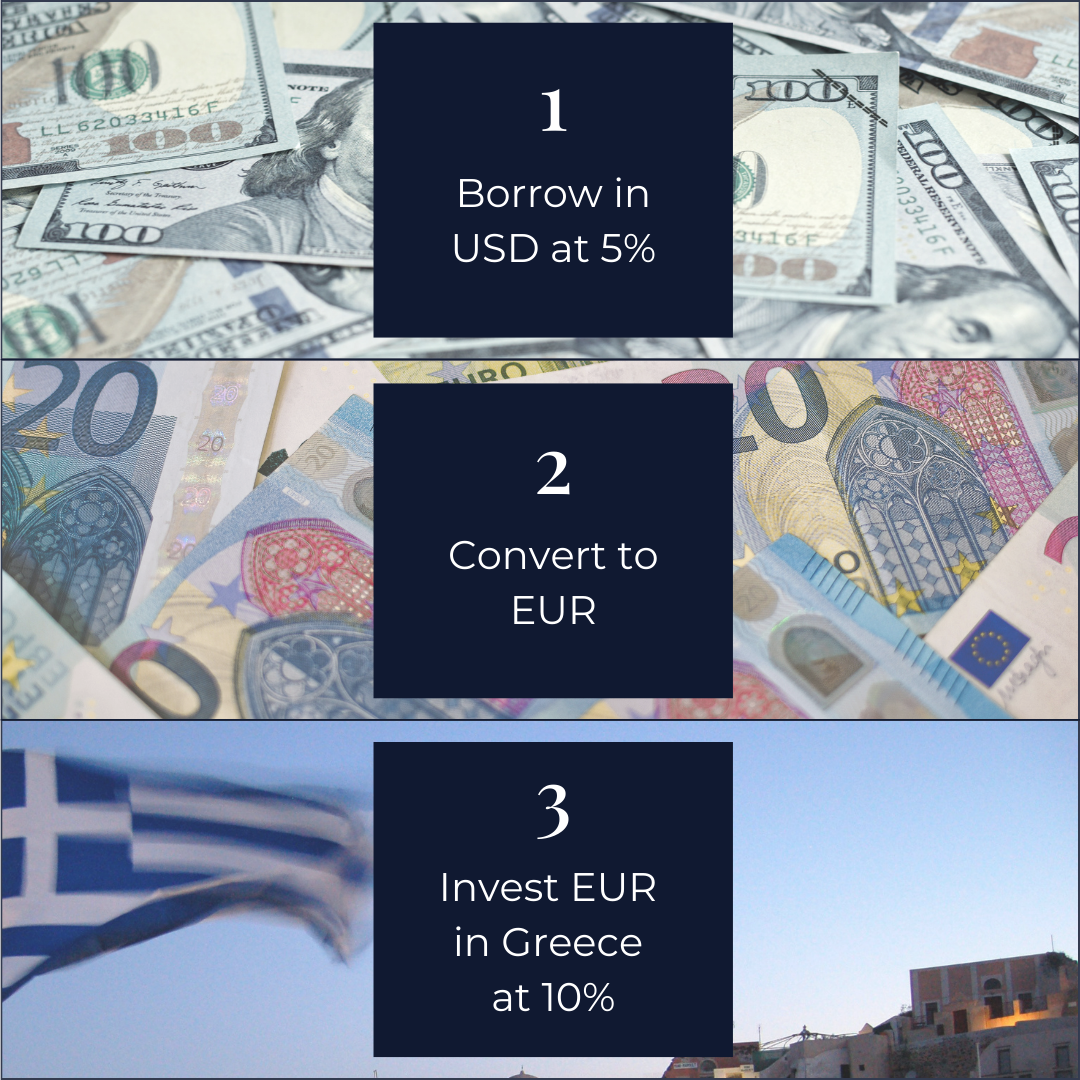

Carry trade is a popular currency transaction where traders, hedge funds and other risk-taking investors borrow in a currency with low interest rates then convert that currency to invest in a country with higher interest rates.

There is a generally accepted principle in economics called purchasing power parity, which states that currency exchange rates should respond to any imbalances by appreciating or depreciating, effectively removing any advantage.

In the graphic below, we’ve created a rudimentary carry trade that, on the surface, would appear to result in a 5% profit because we are borrowing at 5% interest and investing in bonds that pay 10% interest.

In order for the market to eliminate this risk-free trade (often referred to as an arbitrage opportunity), it adjusts the exchange rate. When I convert my EUR profits back to USD, they will buy me less USD. This adjustment is made to account for the fact that one currency is paying a higher interest rate than another.

So, why do traders still use this strategy? The distortion in interest rates over the last decade has made borrowing money cheaper than ever. Because the two currencies are considered to be strong, an extremely popular version of the carry trade is to borrow Japanese Yen (JPY) then invest in USD.

What does this carry trade have to do with recent market volatility? In short, some traders who purchased equities with profits of this carry trade were subject to margin calls, which created a bad feedback loop. Let’s break it down.

- At times, the Bank of Japan (Japan’s Federal Reserve) has enacted policy to make their interest rates negative. Why? That is a story for another day, but this negative interest rate made borrowing in JPY attractive.

- Less-risky traders invested the funds into safe U.S. bonds, like Treasuries. However, some traders were tempted by recent market strength and ultimately invested some proceeds into equities.

- The equity buy-in became an issue in early August when volatility picked up. On top of that, the BOJ raised interest rates on July 31 while markets signaled lower interest rates on the horizon in the U.S.—a double negative for investors in this trade.

Where do margin calls come into this?

- Any time traders borrow, they can be subject to margin calls if the value of their trades start to decline. When the market fluctuates, like it did the week of August 5, these traders can be left exposed.

- This is a bad feedback loop because traders that are in margin calls sell their positions, further depressing prices and pulling others into margin calls.

In the U.S., we experienced a quick volatility spike. In Japan, August 2 and August 5 had a combined pullback of more than 12% in the Nikkei.

Both the Nikkei and the S&P 500 have recovered much of the ground lost over those two days. Although not the only component, the carry trade unwind was certainly a contributing factor to that elevated volatility.

Rest assured that we are on the lookout for further developments within this trade and its impact on the overall market. As always, we are here for you. Do not hesitate to reach out to your Fidelis Capital relationship team with any questions.